Casey Arborway, at Forest Hills in Boston, is a newly constructed roadway with a lot of good features for bikes, transit, and pedestrians, such as cycle tracks, bike signals, relatively small footprint intersections (for the volume of traffic carried), and a left turn lane just for buses.

However, the way its traffic signals are timed results in terrible service — and sometimes unnecessary danger –for pedestrians, bikes and transit.

For those desiring more detail, we have written a full report you can download here which includes recommendations for fixing the problems we found.

Intolerably long delay for multi-stage pedestrian and cyclist crossings at the South Street / Arborway intersection

At the South Street / Casey Arborway intersection, there’s a slip lane for eastbound right turns from Arborway, bordered by a “delta island.” In the leading satellite image, crosswalk C-D crosses the slip lane, connecting the delta island to the nearest corner. If you cross either the east leg or Arborway (A-B-C-D) or the south leg of South Street (D-C-E) on foot or on bike, you have to stop and wait on that delta island. Poor coordination between the pedestrian and bike signals results in outrageously large pedestrian and bike delays.

Crossing Arborway southbound on foot (A-B-C-D)

- First, wait at A for up to 111 s (on average, 48 seconds) to start crossing

- Then stop at the median (B) and wait for 87 seconds

- Then stop at the delta island (C) and wait for 106 seconds

- Finally, get a Walk signal and finish your crossing. Total average delay: 241 seconds, or just over 4 minutes (!!!)

Same crossing on a bike:

- First, wait at A between 0 and 87 seconds (on average, 37 seconds) to start crossing

- Pass through B but stop at C (the delta island) and wait for 84 seconds

- Finally, get a green signal and finish your crossing. Total average delay: 121 seconds, or just over 2 minutes. That’s still double the 60 second limit after which Level of Service is considered “F” (failure).

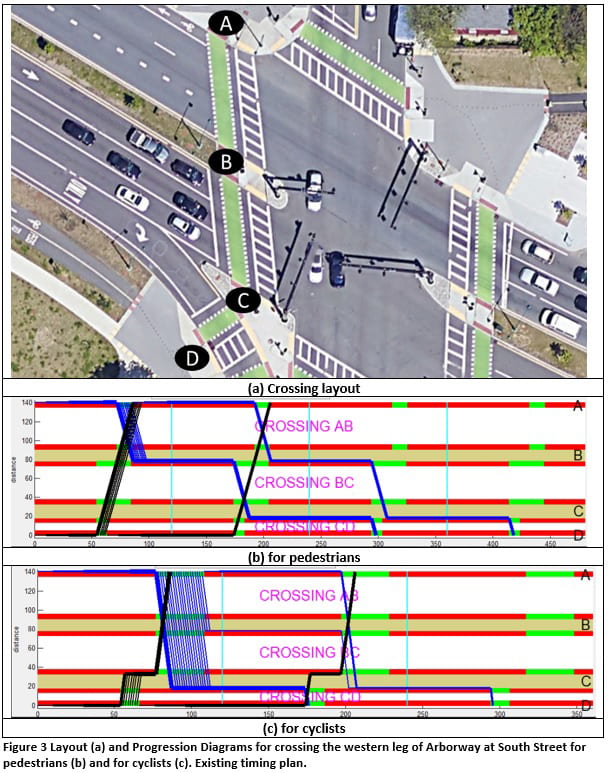

The diagram below shows pedestrian and cyclist progression through the three stages of the crossing. You can see how for people walking southbound (blue lines), people have to stop and wait for a long time on both islands. Pedestrians walking northbound (black lines), in contrast, can pass through without stopping on either island, because for them, the signals line up nicely. The long delay to bikes crossing southbound is also evident.

Figure 3 Layout (a) and Progression Diagrams for crossing the western leg of Arborway at South Street for pedestrians (b) and for cyclists (c). Existing timing plan.

Bad Results Stem from Bad Policy

How could such terrible service be designed, especially in a project that went to considerable expense to include some very nice bike and pedestrian features?

It’s because city and state officials do not require that pedestrian delay be measured and reported when traffic signals are analyzed and designed. The engineers who develop traffic signal plans work hard, optimizing signals to minimize vehicle delay. But they don’t optimize for pedestrian delay, because they never measure it. And because it’s never reported, government officials unwittingly approve designs with pedestrian delays that are completely unacceptable. It’s the old business maxim, “only what’s measured counts.” Pedestrian delay isn’t measured, and so it doesn’t count.

Does it have to be this way?

First, procedurally: Of course not. City and state officials could simply make it a policy that any intersection analysis that reports vehicle delay must also report pedestrian and bicyclist delay. They already require that traffic counts include counts of pedestrians and cyclists; they need to go the next step and require that analysis report on delay to pedestrians and bikes as well as delay to cars.

Second, as far as this intersection’s design: No. Traffic flow not come to a standstill if changes were made to favor pedestrians. In fact, in the report accompanying this post, my grad student Milad Tahmasebi and I show that by making only minor changes to signal timing in order to coordinate the different pedestrian crossing stages with each other, pedestrian delay for the crossing described earlier would fall from 241 to 52 seconds, and bike delay from 121 to 40 seconds. There would be no impact to traffic capacity and no additional delay to cars except for a small increase in delay to cars using the slip lane.

When we shared this report with the Boston Transportation Department, we learned that they plan to retime the signals in the coming fiscal year (starting July, 2021). Great news! But will they get it right the next time? Only if they insist that the analysis include measuring and reporting pedestrian and cyclist delay!

This is not a new issue. When the Landmark interchange (formerly called the Sears Rotary) was rebuilt around 2012, I saw a preview of the signal plan, and wrote to the responsible officials, telling them average pedestrian delay would be more than 120 seconds, including waiting 30 seconds on one island and 60 seconds on the next one. The design went ahead anyway, and almost ten years later, the intersection still operates like that. One of my students has shown how with small changes to the traffic signal plan in order to coordinate pedestrian signals, average pedestrian delay there could be reduced from 123 seconds to 40 seconds with no change in service to autos. And in 2007, Beacon Street in Brookline got all new intersections and traffic signals. It was supposed to be a pro-pedestrian project, yet pedestrian delay for some of the Beacon Street crossings is more than 100 seconds because the pedestrian phases for crossing to and from the median island are not coordinated. One of my students and I analyzed it, and sure enough, with small adjustments that better coordinate the pedestrian signals, pedestrian delay would fall by more than 60% without any noticeable impact on auto traffic.

Is it always this bad? Thankfully, no. Where intersections have simple, one-stage crossings, with pedestrians walking concurrently with autos, average pedestrian delay isn’t terrible, and both designers and officials responsible for approving signal timing plans have a rough idea of whether pedestrian delay will be long or short because they know it’s closely related to the length of the signal cycle (which is reported). The outrageously long delays I write about here are always at intersections where pedestrians cross in two or more stages. Where there are multistage crossings, pedestrian delay depends greatly on how well coordinated are the pedestrian phases. If coordinated well, service can be reasonably good; if not, it can be a total disaster. So it’s intersections with multistage crossings that would most benefit from a policy requiring that pedestrian and bike delay be reported in any analysis in which vehicle delay is reported.

Don’t engineers need the tools to measure pedestrian delay? Yes, of course. Unfortunately, the commerical software they use for intersection analysis and signal timing, Synchro, doesn’t measure pedestrian delay.

For simple, single-stage crossings, pedestrian delay can be calculated using a simple formula that’s in the Highway Capacity Manual and is therefore well known. But there is no simple formula where pedestrians make a multi-stage crossing.

So I made a tool that will calculate average pedestrian (or bike) delay. It can handle crossings with up to four stages. It’s free and has been available via this web site since 2017. Please use it.

Back to the Intersection of South Street with Arborway …

The crossings across the southern leg of South Street are similarly affected by poor coordination between the crossing phases. Eastbound pedestrians currently have an average crossing delay of 108 seconds, including a 57 second wait on the delta island next to the slip lane. In the better coordinated plan we propose, their average delay falls to 32 seconds.

The signal timing plan there also has a feature called a leading pedestrian interval (LPI) which is supposed to protect pedestrians from turning vehicles, but in this case is endangering them instead. The LPI is part of the signal phase for South Street southbound, which means that pedestrians in the adjacent crosswalk (who are crossing Arborway) get a Walk signal 5 seconds before cars get a green. In general, LPIs help pedestrians establish their priority over right turning cars by giving them a head start to reach the conflict zone. However, in this case, there are hardly any right turning cars to be protected from (and they go slowly because of the sharp turn angle). More importantly, during that LPI, northbound left-turning cars are allowed to proceed, because their phase starts earlier and overlaps with the southbound phase; and those left-turning cars create far greater danger to pedestrians, since they turn much faster, with a less predictable path, and with far greater volume. There is a simple fix: Eliminate that LPI. Pedestrians need southbound cars to be released simultaneously with pedestrians to protect them from the left turn danger.

At the intersection of Washington Street with Arborway: Need Fixes for Buses, Pedestrians, and Bikes

At the Washington / Casey Arborway intersection, three issues were detected.

First, abuse of a bus-only left turn phase is leaving some buses waiting up to 6 minutes to make their left turn. Drivers are blatantly violated the “No Left Turn Except Buses” signs. And because the left turn phase is timed with only enough green time for two or three buses per cycle, when cars join the queue, buses sometimes wait for 2, 3, or 4 signal cycles till they can finally pass through.

Second, pedestrians crossing northbound have the opposite of an LPI – right turns go first, and then pedestrians are expected to start walking into an established right turn flow. Letting pedestrians begin concurrently with vehicles instead of delayed by 12 seconds, as they are now, can alleviate this problem.

Third, in the east-west direction, bike phases are red during the LPI, even though bikes need the same protection as pedestrians from turning cars. The bike signals should be adjusted so that bikes can go during the LPI.

Want more detail? See the full report.