Click here for traffic simulation of the proposed layout

Cummins Highway, between Mattapan Square and the cemeteries just west of Wood Ave. / Harvard St., is an auto-oriented, 4-lane divided road passing through the middle of Boston’s Mattapan neighborhood. In one way, Cummins Highway serves the neighborhood by providing access to bordering towns and neighborhoods. But in many other ways, this road does a lot of harm to the community through which it passes, including:

- Speeding. Its layout facilitates speeding, even racing, with a significant proportion of traffic going faster than 40 mph. During much of the day, traffic is light. Because there are two lanes in each direction, drivers can easily pass others and easily achieve dangerously high speeds.

- Dangerous crossings. Pedestrian crossings are long and dangerous, though (fortunately) broken by a median. Because of the multi-lane layout, motorists rarely yield to pedestrians waiting at a crosswalk. And when they do, that poses a danger known as a double-threat — the car that stops for you in lane 1 may screen you from an approaching car in lane 2. Parents do not feel safe letting their children cross to get to elementary school or other destinations.

- Missing crossings. At several bus stops, no crossings are provided at all, even though it is well known that at every bus stop, 50% of the passengers getting on or off have to cross the street..

- No safe place to ride a bike. There are no bicycling facilities at all. Cyclists either use the sidewalk, which has poor sight lines and is intended for pedestrians, or ride in the road, sharing a lane with fast traffic.

- A particularly large and dangerous intersection. At Greenfield Rd, the oblique turning angle makes it possible for cars to turn into a neighborhood street at high speed. The corresponding left turn, from Greenfield onto Cummins, is dangerous because the angle makes it difficult to see and judge approaching traffic. The intersection’s huge, open paved area adds to the confusion and makes it difficult for pedestrians to cross.

- It is ugly and *not* green. Cummins Highway cuts a wide swath of ugly, barren pavement through the neighborhood. With no grass and almost no street trees, it is unattractive as a walking route. It could be transformed into more of a parkway, where people would enjoy walking and bicycling.

Study Objective. This study tests whether it is feasible to convert Cummins Highway into a street that serves, instead of severs, its neighborhood. The objective is to find a design that solves the six problems just described without sacrificing the road’s valuable mobility function.

In practical terms, the key to meeting these six objectives is a “road diet,” meaning reducing the road from 4 lanes to 2. That will limit speeding (you can’t speed when there’s a car ahead of you that you can’t pass); it will make crossing easy and safe; and it frees space for bike lanes and for street trees. But will one lane per direction be enough to carry the traffic?

This study has two major dimensions: traffic capacity and street layout. It examines the traffic volumes and traffic signal settings to see whether a two-lane layout can carry the traffic, and where extra travel lanes may be needed at bottlenecks. And it explores the road layout to see whether, within the existing right of way, all the desired features can fit: sidewalks, bike lanes, street trees, parking lanes, bulbouts to shorten crossing distances, a median to keep crossings simple and safe, and bus stops with safe crossings.

Traffic Volume Data

Existing traffic counts (a.m. and p.m. peak hours) were available for the four signalized intersections with significant cross traffic. Because the p.m. peak showed the greatest hourly volume, this study uses p.m. peak hour volumes. And because the existing counts date from 2012, a fresh count was done in October, 2018 at the corridor’s peak volume point (Cummins Highway @ Harvard St / Wood Ave), which showed a 5% increase compared to the 2012 counts; therefore, the existing counts for the other intersections were scaled up by 5%.

Appendix A contains detail on traffic volumes used in the analysis.

Features of the Proposed Design

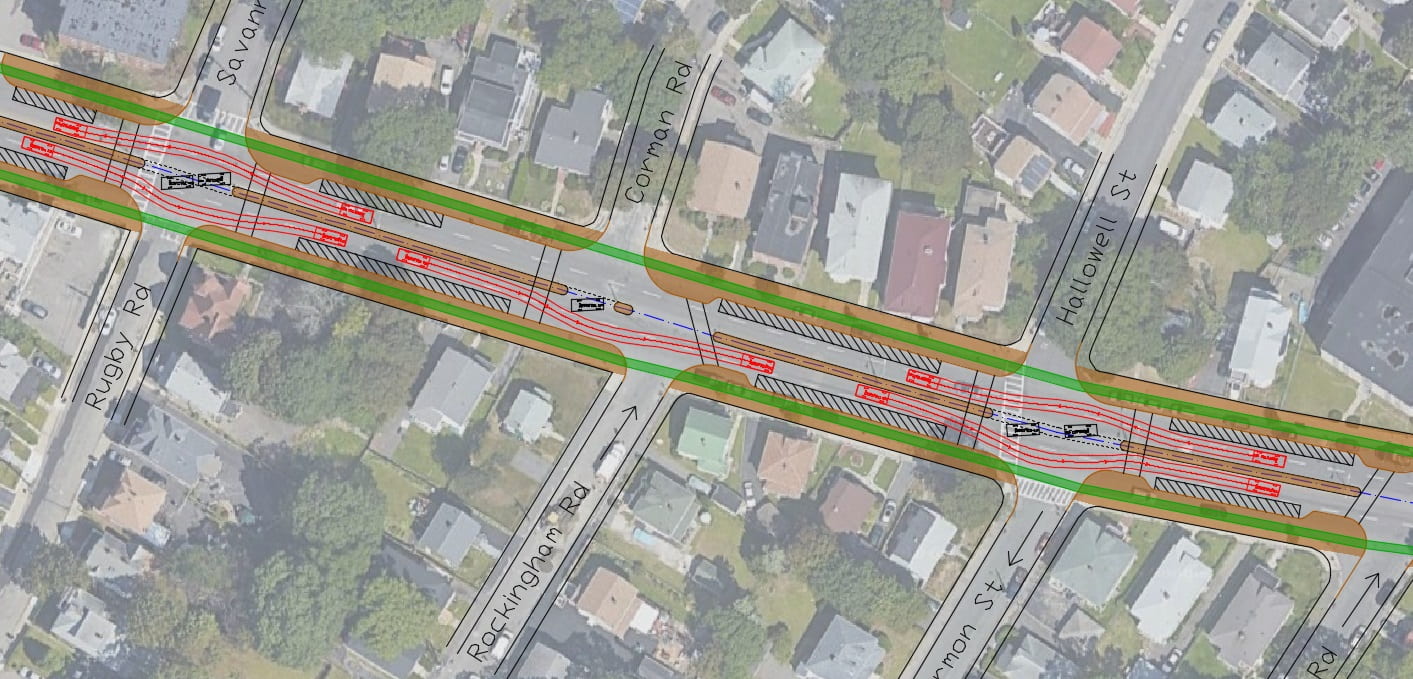

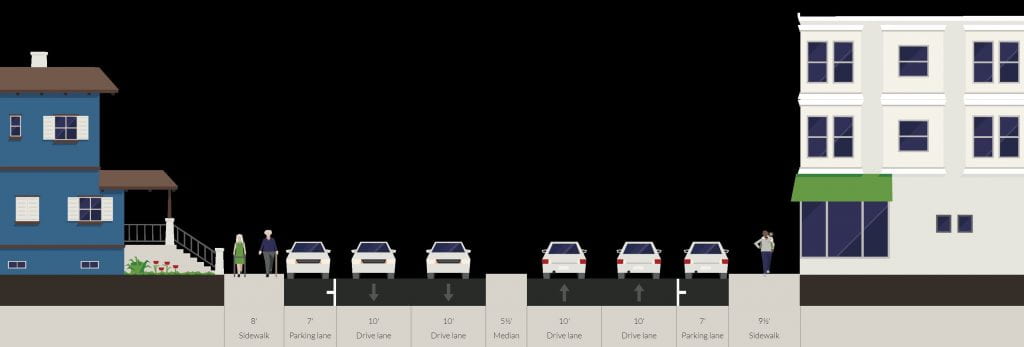

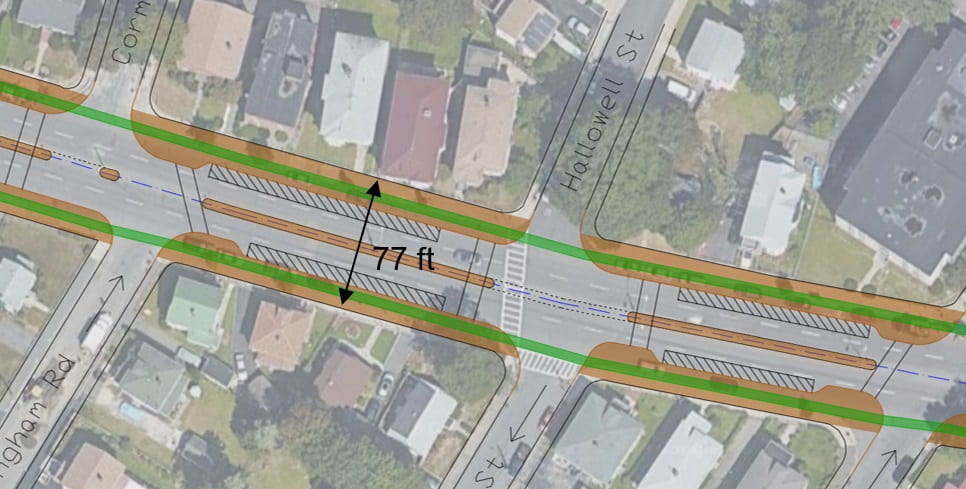

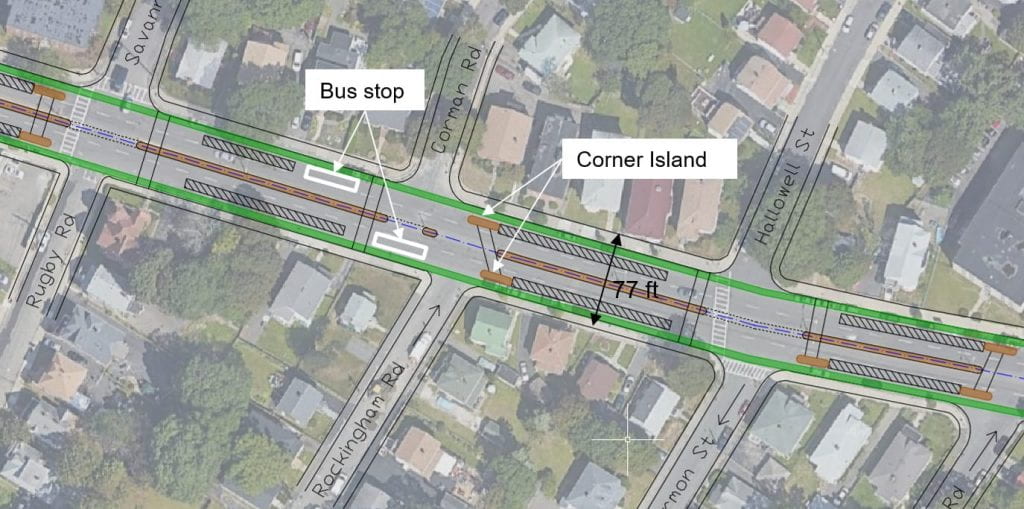

Existing Basic Layout. The road’s existing basic layout has, in each direction, two travel lanes and a parking lane. The two directions are separated by a narrow raised median. There is no bike lane. There are sidewalks on both sides, usually 8 to 10 ft wide, with almost no trees. Right of way is 80 ft wide in the western part the corridor, narrower as the road gets closer to Mattapan Square. Figures 1 and 2 show the existing layout between Hallowell St and Rockingham Rd, where the right-of-way width is 77 ft .

Figure 1 – Existing layout with 77-ft right of way

Figure 2 – Existing cross section with 77-ft ROW

Proposed Basic Layout. As proposed, the basic layout preserves the parking lanes and median, but has only one travel lane per direction, as shown in Figures 3 and 4 for the same stretch of road whose existing layout is in Figures 1 and 2. The sidewalk area on each side of the street is enlarged to about 16 ft and subdivided into three parts: a tree belt or planting strip, a one-way cycle track (bike path), and a walking zone. Where right of way is narrower or wider than 77 ft, the difference is put into making the planting strip narrower or wider. For more details, see link to overall plan drawing and link to detailed drawings.

Figure 3 – Proposed layout (77-ft right of way)

Figure 4 – Proposed cross section (77-ft right of way)

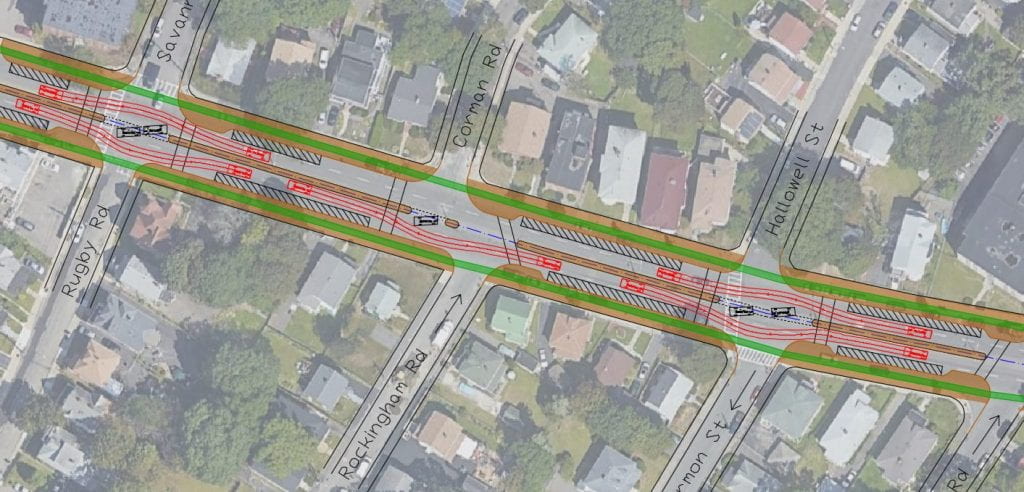

Features at signalized intersections: Turn pockets, extra through lanes, and left turn restrictions. At four signalized intersections, to get the needed traffic capacity to make a road diet work, turn pockets and, in some cases, extra through lanes are added, as listed in Table 1. Where an extra through lane is needed, it is roughly two blocks long on either side of the intersection to give traffic space to queue and to merge back to a single lane.

For the intersection at Harvard / Wood, we propose adding a left turn prohibition westbound from Cummins Highway onto Wood Avenue. There is little demand for this left turn (only 1 vehicle every 2 minutes in the peak hour), yet the blockage it causes creates a capacity bottleneck because the road doesn’t have the width needed to make a left turn pocket. The few vehicles with that desire line can instead turn left onto Tampa Street or Seminole Street.

Features at unsignalized intersections: Informal flares to prevent blocking through traffic. At unsignalized intersections, the proposed design provides enough clear roadway space so that left turning vehicles can wait without blocking traffic (Figure 5). This clear roadway space, called an informal flare, comes about by a combination of opening the median and prohibiting parking near the crosswalks. These informal flares are critical for enabling a single lane to carry the traffic that is now being carried by two lanes.

Figure 5 – Passenger vehicle paths (in red) going around cars stopped to make a left turn (informal flare function). Drawn using AutoTURN.

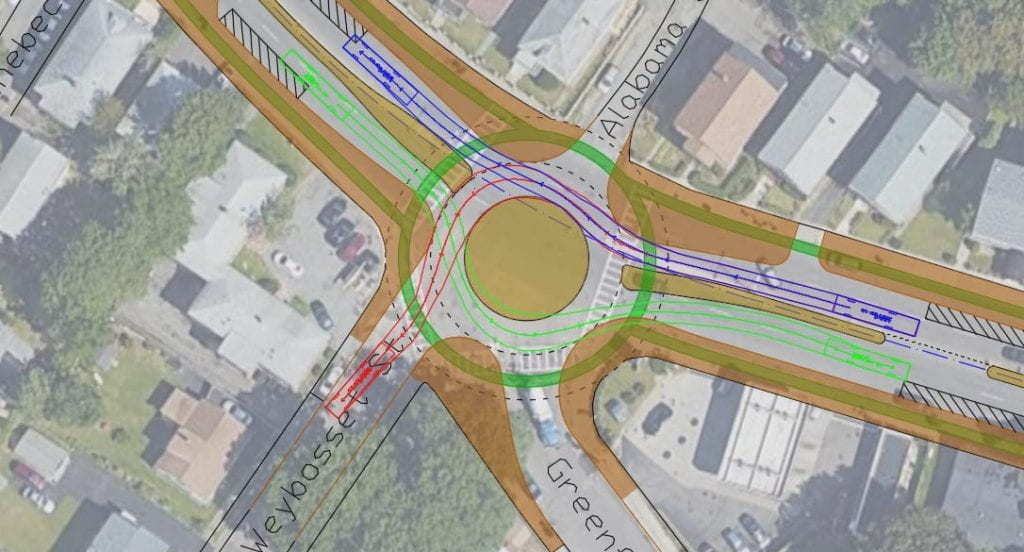

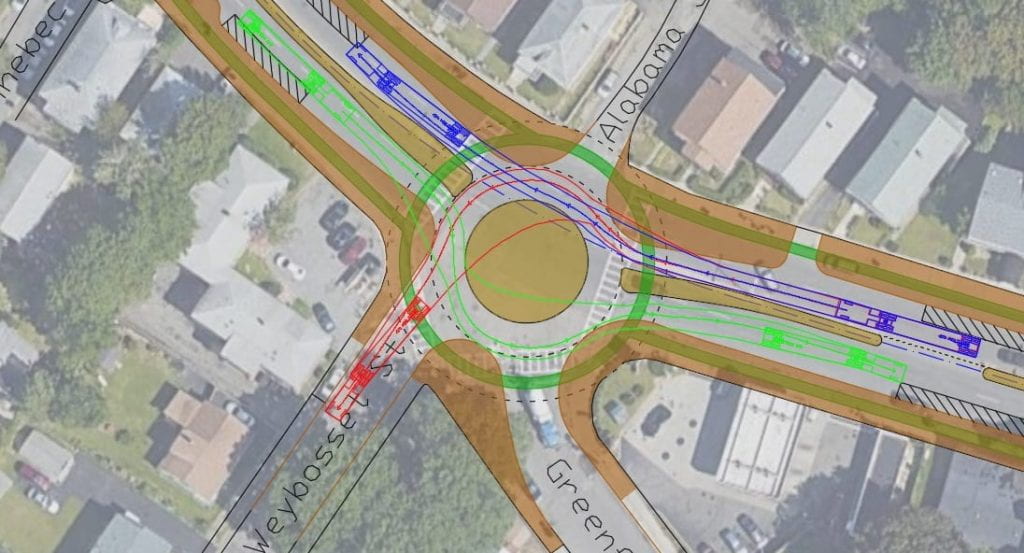

Mini-roundabout at Greenfield Rd / Weybosset St. At the large and dangerous five-leg intersection of Cummins Hwy / Greenfield Rd / Weybosset St / Alabama St, a miniroundabout is proposed. With an inscribed diameter of 90 ft and a circulating lane of 16 ft wide, it will allow cars to pass through without touching the median (Figure 6), while at the same time forcing enough deflection to ensure that cars pass through at a speed of about 15 mph. However, school buses and large trucks (e.g., 62-ft long tractor trailers known as WB-62) will have to slow down further and let their rear wheels track over the center island and the “armpits”. For this function, the curbs for center island and “armpits” will have a 3″ vertical face, which will deter cars from using them, but which slow-moving buses and trucks with large wheels can mount (Figure 7). That mountable feature makes it a “mini”-roundabout.

Figure 6 – Large school bus (S-Bus-40) vehicle paths for left turn (in red) and through movement (in green and blue) going through the proposed roundabout (drawn using AutoTURN)

Figure 7 – 62-ft long tractor trailer (WB-62) vehicle paths for left turn (in red) and through movement (in green and blue) going through the proposed roundabout (drawn using AutoTURN)

Statistically, single lane, small-diameter roundabouts like this typically reduce injury crashes by 80%. For pedestrians, the proposed roundabout has much shorter crossings (13 ft across each direction of Cummins Hwy and 20-30 feet across the other streets, versus crossings of 60 – 100 ft today). For bike safety, there is a 10-ft offset between the circulating lane and the cycle track, improving visibility and giving both motorist and cyclist time to react in case of a conflict.

A roundabout provides ideal speed control for a road like Cummins Highway – it doesn’t force vehicles to stop, but it forces all vehicles to slow down. It eliminates the existing high-speed right turn onto Greenfield Rd and the dangerous low-angle left turn from Greenfield onto Cummins.

Two traffic signals are removed. Traffic signals are proposed for removal at 610 Cummins and at Rockdale Street. The existing signals there were installed to facilitate pedestrians crossing a 4-lane road. With the new 2-lane design with crossing islands, crossings will be safe without a traffic signal, and so the signals can be removed. This change actually improves pedestrian service, because with a simple crosswalk, pedestrians will be able to cross with almost no wait at all, instead of having to wait for a WALK signal.

Relocated bus stops with safe crossings. Some bus stops have been relocated with a goal of ensuring safe crossings. For example, a traffic signal was recently added at the Itasca / Ridlon intersection, but there is no bus stop there now to take advantage of this safe crossing; our design places a bus stop there. In some cases, closely-spaced stops have been consolidated. The proposed stop locations have a stop spacing between 600 and 950 ft, which is the right balance between easy access and efficient service.

Traffic Analysis Results

To test whether the road diet solution can carry the traffic now carried by Cummins Highway, analysis was done using two software tools: Synchro, which does formula-based capacity analysis, and Vissim, a finer-grained traffic simulation software.

The Synchro analysis shows that the proposed layout offers both sufficient capacity and good level of service – that is, reasonably short delay – at each of the corridor’s signalized intersections. Cycle lengths are relatively short as well, reducing pedestrian delay. Results are in Table 1; for greater detail, see link to Synchro results and link to Vissim traffic simulation.

Table 1 – Summary of intersection analysis and lane configurations

[Explanation of the last column: v/c is volume / capacity ratio. A value less than 1 indicates sufficient capacity. At a signalized intersection, each traffic movement (e.g., eastbound through, eastbound left, …) has a v/c ratio. “Max v/c” is the worst v/c at the intersection, that is, the v/c for that intersection’s most congested movement. For example, if Max v/c = 0.88, it means that every traffic movement at that intersection has a v/c ratio of 0.88 or lower.]

Level of service at the proposed roundabout was not measured with formulas; however, simulation results show a good level of service, with average delay around 10 seconds for both Cummins Highway and side street traffic.

Summary of Benefits

Speed Control: The proposed layout will help control vehicular speeds in four ways.

- By preventing passing. Drivers who want to speed will be constrained by the vehicles in front of them.

- By making the roadway much narrower – only 1 lane per direction instead of two, and only 13 feet between the median and the parking lane.

- The roundabout at Greenfield Rd will reduce speed to about 15 mph there, and will help prevent speeding in its vicinity.

- The short signal cycles this layout makes possible (60 s at Woodhaven and at Itasca, 80 s at Harvard / Wood) help reduce speeding by reducing the amount of “wide open green time” at intersections (time when the signal is green and there is no longer a discharging queue).

Safer Pedestrian Crossings: The proposed road diet has a lot of safety benefits for crossing pedestrians:

- The proposed layout adds 11 new crosswalks. There will be safe crosswalks at every bus stop.

- Crosswalk length is reduced substantially. For instance, at Savannah Ave/Rugby Rd, the full crossing will be shortened from 63 ft to 40 ft overall, and the lengths of the half-crossings (between median and curb) will be reduced from 30 ft to 17 ft.

- The “double threat” disappears. In the existing 4-lane layout, a car stopping for a pedestrian in lane 1 can screen a pedestrian from an approaching car in lane 2, creating a high crash risk. That double threat disappears in the road diet layout. When a car stops for you, you’re 100% safe to cross to the median, and then when the next car stops, you’re 100% safe to complete your crossing.

- Vehicle compliance at crosswalks (yielding to pedestrians waiting to cross), which is notoriously poor on multilane roads, will become much better when cars are in a single lane per direction, separated by a crossing island.

Tree belts: Today’s Cummins Highway is noticeably bare of vegetation. Our layout includes a 5-ft tree belt on each side of the street, providing shade to pedestrians and cyclists and improving the beauty of the neighborhood.

Protected bike lanes: The proposed design has a one-way cycle track (also called protected bike lane) on each side of the street. Cycle tracks will be at sidewalk level, separated from traffic by a curb, a parking lane, and tree-lined buffer. Because of this separation from traffic, bicycling will be safe and attractive for all, including children.

Some traffic signals become unnecessary: Thanks to safer and shorter crosswalks, the two existing traffic signals that are currently used only to stop the traffic for crossing pedestrians (at Rockdale St and at 610 Cummins, between Kennebec St and Hebron St) can be eliminated. Pedestrians there will have less delay than now, because they will have right of way at all times. The narrow roadway layout and low traffic speeds engendered by this design make it highly likely that motorists will comply and yield to pedestrians.

Overall vehicular travel time and delay: Average delay at signalized intersections will decrease because of the lower cycle length and because two signals are removed; however, traffic will go slower between signalized intersections. Overall, our simulation model predicts that average travel time between Mattapan Square (not counting signal delay there) and a point just west of Wood Ave. (and thus including delay at the Wood Ave. intersection) will be 3.5 minutes, corresponding to an average speed of 16 mph. This study did not model existing conditions using simulation, and so cannot directly calculate a change in overall vehicular travel time and delay, but the change is expected to be near zero. For comparison, average speed on urban streets, including intersection and traffic delays, is typically 9 to 13 mph.

Cost Considerations

The proposed layout leaves median intact, but shifts the curbs inward. That will necessitate new drains, new sidewalks, new pavement for protected bike lanes, and a new tree belt. We have not estimated the cost of these changes. On top of that, construction of a new roundabout will add about $250,000 to the cost.

Less Expensive Option

A temporary, less expensive option is also possible — leaving the curbs and sidewalk intact as well as the median. Most of the features of the full design can still be retained except the tree belt. Protected bike lanes will be at street level, separated from moving traffic by a row of parked cars and a hatched buffer zone with plastic posts (bollards). At unsignalized intersections, plastic bollards will be used to create pedestrian islands within the parking lane at the ends of each block, so that pedestrian crossings will be short.

Another low-cost option — more costly that what was just described but still low-cost as road reconstruction projects go — would be to install raised pedestrian islands within the parking lanes (Figure 8).

Figure 8 – Proposed intermediate cost option